Whether you are of Russian heritage but too young to really remember the fall of the Soviet Union, or an American of any age trying to understand the Trumpian embrace of Vladimir Putin, there is a renewed interest by both Russians and Americans in how Russia traversed from the chaotic but hopeful Yeltsin era to the Russia of today.

Americans really do need to take a renewed look at Russia. For starters, the popularity of Putin among Russians is genuine. The pride and patriotism is genuine. The relief that the embarrassing chapter of the Boris Yeltsin era is over is palatable. That this renewed strength in Russia comes at the expense of personal freedoms is without a doubt. That it comes with a U-turn back to a centralized economy with little tolerance for entrepreneurial, competitive markets and conflicting power bases is also without a doubt. Some Russians care. Most do not.

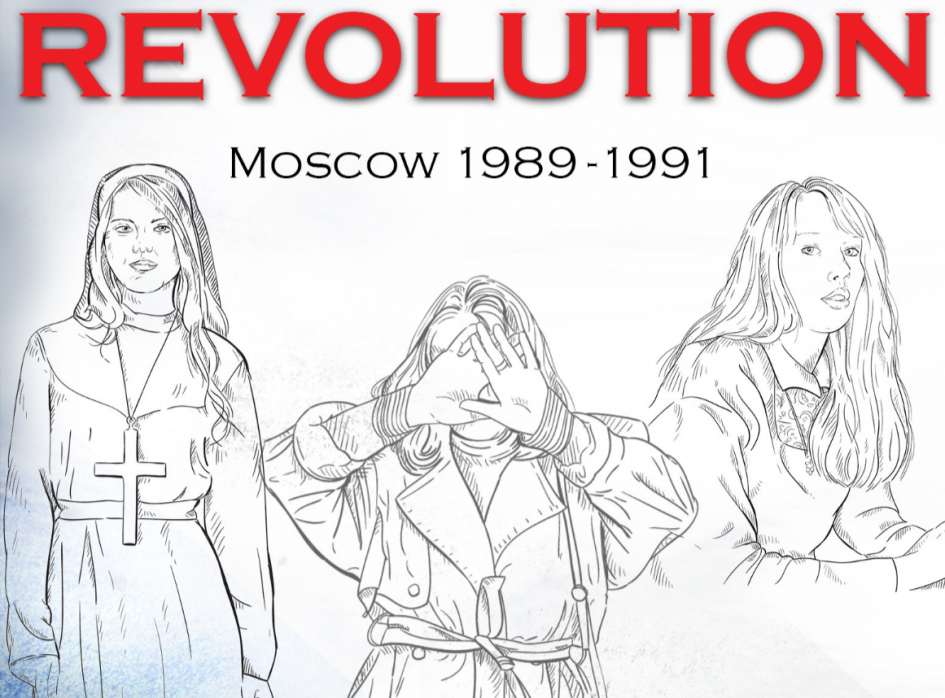

To understand Russia today you have to clearly understand what happened to the Russian people themselves as the Soviet Union fell apart. And that is the objective of my just-published memoir, “Three Sisters at the Revolution.” The book chronicles what I saw from 1989-1992 as the Soviet Union was crumbling. Not the famous political details of the interplay between George H.W. Bush, Margaret Thatcher, Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin, but how the collapse of the Soviet government impacted the lives of everyday people. The focus of my stories is three extraordinary women: Olga, Little Irena and the woman I called Crazy Irena.

I arrived in Moscow in December of 1989 in order to witness a rocket launch to the Russian space station. The rocket was carrying the first commercial American payload, a biomedical research project. I had helped the companies involved receive the U.S. government permission, a story I tell in my earlier book “Selling Peace.”

But I ended up seeing far more than a launch. As I chronicle in “Three Sisters,” I witnessed the clash between the onslaughts of American values against those Russian. Accepted concepts for us, like freedom of religions, weak governments and free markets were at first intoxicating to the Russian people. Our way of life was embraced as the antidote for the Soviet system. The three sisters dreamt of going to America, of worshipping in our churches and being independent women, as they understood existed in the States. But then it all began to go wrong.

We Americans wholeheartedly embraced Gorbachev, we embraced the selling off of their governmental institutions. We turned a blind eye to the rise of the mafia. We thought little what it must be like to have our own children speaking in a foreign language and our daughters and sons making far more money than the parents. We never understood just how threatening the idea of American evangelists preaching a cacophony of religions at the expense of the Russian Orthodox Church. The long subtitle of my work sums up my feeling: “An Eyewitness Account of how the Export of Freedoms Produced the Russia of Today.”

Another character in the book is well, myself. Through the main character, Olga, I came to understand far better what it means to be an American, and to be Jewish. With the help of Olga and her own understanding of being partly Jewish, I journeyed full circle, back to my grandparents to realize how unique is our own country and my own family’s journey. But also that it is not always possible to export our own values to other lands and expect acceptance.

Whether in the Russia of the 1990s or Iraq and Afghanistan a decade later. And sometimes, just sometimes, the most wonderful of decisions is to stay in your own homeland, with your own family, rather than start again somewhere unknown. A decision that Olga finally made.

By 1992 each of the women was rejecting America’s remaking of their society in our own image. Their dreams slipped away in the reality of scarce foods and myriad alien choices. My friends mirrored many in Russia.

Putin is clearly understood by Russians, whether they support him or do not. But for Americans, his popularity is often misunderstood. I hope my memoir of my own experiences and journey helps explain one part of the puzzle of just how the Russia of today came about.

Jeffrey Manber – Washington, DC, 2016